A Diaspora View of Africa

Biden’s Africa Policy is Laudable But Lacks Context

By Gregory Simpkins

By Gregory Simpkins

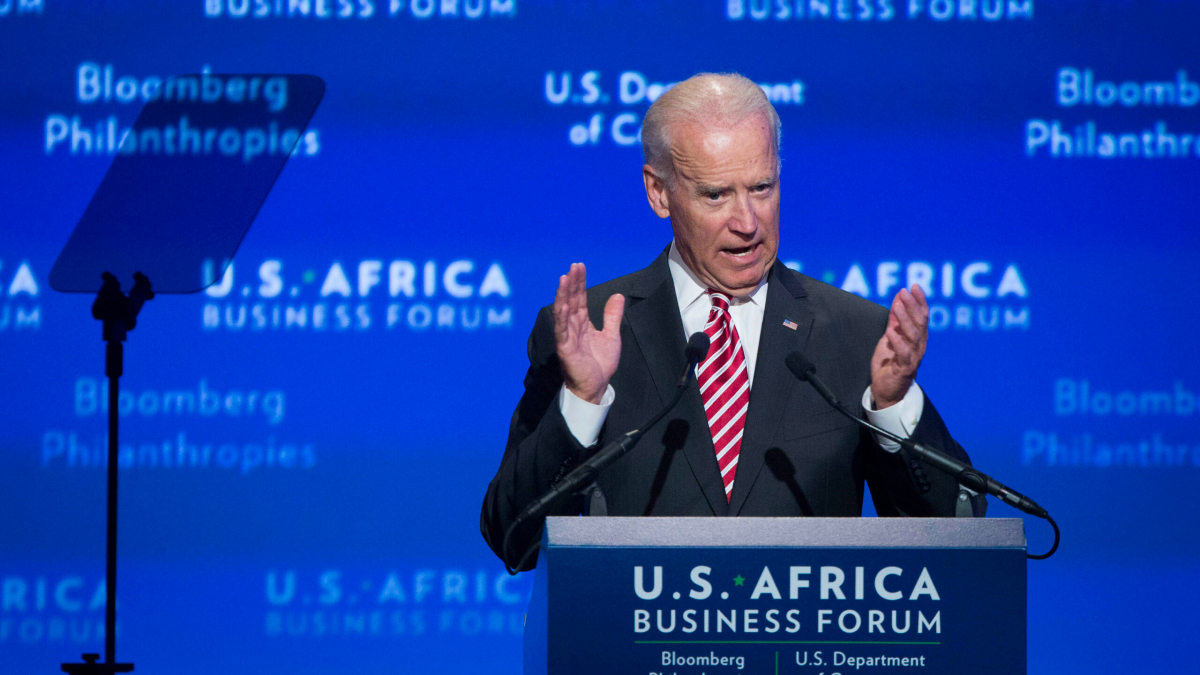

The Biden Administration has released its U.S.-Africa policy document, and it looks a lot like the previous ones issued by American Executive Branch officials. That’s not necessarily a criticism, though, because what should be done and what needs to be done regarding our country’s Africa policy isn’t difficult to understand. As the saying goes: it isn’t rocket science. However, similar policy prescriptions I’ve seen over the last four decades have been only partially successful for reasons I will discuss shortly.

The Biden plan acknowledges the importance Africa plays, as highlighted in a November 21 speech by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who said: “Africa will shape the future —and not just the future of the African people but of the world.”

True as that statement is, the sentiment hasn’t been reflected in U.S. policy toward the continent. Even the Biden Administration is focusing on the pivot to Asia due to competition with China for primacy in the region, but Africa is where much of our competition with China really is playing out.

For example, the strategy document states that 30% of the world’s critical minerals come from Africa. In point of fact, Africa is the source of strategic minerals and other resources in significant percentages that the modern world cannot do without, such as platinum (75 percent), coltan (68 percent), cobalt (58 percent from the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone), diamonds (46 percent) and gold (21 percent). Neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy), and terbium (Tb) are key elements in the composition of the NdFeB permanent magnet used in the latest generation of solar panels and wind power technology.

Without these minerals, the modern world as we know it could not function. Unfortunately, successive U.S. administrations have lost the U.S. predominance, for example, in cobalt from the Democratic Republic of the Congo – 100% of which is now controlled by China.

So, when we talk of moving to renewable sources of energy, we must keep in mind that China controls not only cobalt but also the refinement of other vital mineral products. China, which has increasingly attempted to lock up much of the supply of strategic minerals from African countries, is now the leading producer of what are known as rare earth elements or rare earth metals.

These are 17 chemical elements in the periodic table, which are used in various technological devices, such as superconductors, electronic polishers, refining catalysts, and hybrid car components. As time goes on, these minerals will increase in importance in the 21st-century economy.

China now represents 95% of rare earth supplies. There will be no clean energy revolution without going through China, and the more global economies move in that direction, the greater China’s leverage will be over the rest of the world.

This situation did not happen during the current administration. Former House Africa Subcommittee Chairman Ed Royce, for whom I worked at the time, said 25 years ago that Africa mattered partly because of its natural resources. That was during the administration of President Bill Clinton, and his officials, as well as those in every administration since then, heard that, but still let control of these minerals move to Chinese control.

Now the Biden Administration faces the task of dealing with two competing situations: moving to renewable energy while competing with an aggressive country that controls the elements that make that transition possible.

The four policy objectives of the Biden plan are the following: to foster openness and open societies, deliver democratic and security dividends, advance pandemic recovery and economic opportunity, and support conservation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition.

The recommendations to achieve these goals are reasonable on their face. However, they are expressed without any acknowledgment that African countries aren’t starting from the same place as we are. Moreover, there is no realization of the vast cultural differences that make fulfilling these goals often extremely difficult.

Our country was never a colonial power, despite the linkage between the United States and Liberia due to those freed slaves who returned home in the mid-1800s. U.S. governments have had a long alliance with successive Liberian governments but Liberians feel a kinship to America that Americans don’t feel toward Liberia. However, if Americans don’t understand Liberia, how can they be expected to understand people in the rest of the continent?

The new policy calls for the government to “increase its focus on rule of law, justice, and dignity to deepen resilience and undercut negative influences.” Successive U.S. administrations have been trying to achieve this goal by offering incentives for African governments to make necessary reforms and then punishing those who refuse or fail to do so.

Colonialism skewed the way African governments ran their countries. Therefore, Prosper Africa is such an advance over previous policies calling for reforms because to entice reforms, it offers visible commercial opportunities that require the reforms presented to unlock.

Telling governments that they should abide by international standards has never been completely successful without outside inducements from development finance agencies and inside pressure from the private sector and civil society. That’s what helped during the 1990s wave of democracy in Africa, and it is what will be necessary in this case.

Delivering democratic and security dividends by “backing civil society, including activists, workers, and reform-minded leaders; empowering marginalized groups, such as LGBTQI+ individuals; centering the voices of women and youth in reform efforts; defending free and fair elections as necessary but insufficient components of vibrant democracies” is fraught with cultural problems.

African societies are not uniformly at the same place of understanding and acceptance of these issues as we are in the United States, and even here there is no uniformity on these issues. We have made significant progress in enhancing the role of women and youth, but there are still issues to be overcome.

Our society is still really at the beginning of successfully addressing and integrating LGBTQ+ concerns into full acceptance in the greater American society. I have seen confrontations between U.S. government officials and African government officials over issues such as homosexuality and attempting to force the issue through threats of sanctions hasn’t worked.

It took the United States centuries to come to the point where we are now, and to expect African societies to come to the point where we are now overnight is far more than should be reasonably expected. That doesn’t mean our efforts are unwarranted, but there must be realistic expectations of success on short timetables and strategies for moving the issues while minimizing conflict.

The effort to advance pandemic recovery and economic opportunity began during the last administration, but recovery has been limited by the constraints of African and international policies designed to prevent the spread of disease and now are exacerbated by the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Any policy we design must acknowledge the possibility of unexpected situations such as the war in Ukraine. Furthermore, any recovery effort, especially those focusing on enhanced resilience to situations such as pandemics and natural disasters, must help African governments and societies build self-sufficiency to the greatest extent possible.

When the rest of the world is suffering at the same time, aid is often not as forthcoming as the needs require. “Closing critical gaps in African countries’ pandemic preparedness and response capacities is pivotal to U.S. and global health security,” the policy states.

Over the years, diseases such as AIDS, Zika, West Nile Virus, and now Monkeypox have existed in Africa for decades. It has only been when these diseases broke through to the global population that they began to be effectively addressed. For this phase of the policy to work, we must care about diseases before they affect those outside Africa.

Finally, the effort to support conservation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition carries with it serious complications and calls for our government “to support just energy transitions in line with their economic and social objectives” as well as to “harness U.S. and African private sector investment to support the energy transition, enable energy diversification, and promote energy security, climate objectives, and economic development.”

The Biden Administration may be convinced that we can shut down fossil fuel production in our country, but African governments have no intention of abandoning resources critical to their economic development, especially at a time when the embargo and shutdown of Russian natural gas to Europe provides significant opportunities for filling that gap.

All countries should look to a future of renewable energy, but African fossil fuel producers won’t be welcoming to any U.S. policy that encourages them or forces them to give up sources of energy they see as valuable to their present and near future.

One especially bright spot in the Biden policy is its acknowledgment of the valuable role the African Diaspora can play as a bridge between our country and countries in Africa. It is as true today as it was when I wrote that in the first Prosper Africa policy paper from the U.S. Agency for International Development in 2018.

Diaspora people born in this country and those who have emigrated from the continent to become citizens here can be the vanguard of economic and social opportunities for other Americans. Collectively we have more than a trillion dollars in potential investment resources.

Additionally, those of us who can demonstrate success in trading with Africans and investing in their ventures can use our relationships here and with those on the continent to create linkages that might not happen otherwise.

The Biden policy states that: “We will elevate our Diaspora engagement to strengthen the dialogue between U.S. officials and the Diaspora in the United States. We will also support the UN’s Permanent Forum for People of African Descent. Through these efforts, we will seek to better highlight U.S. policies, combat misinformation, foster partnerships, and deepen mutual understanding.”

This goes beyond previous U.S. government statements on Diaspora policy, and if this element is carried out effectively, significant progress can be made in creating enduring linkages between the United States and the countries of Africa.

It is always welcome to see the U.S. government express an interest in better relations with Africa, and if consistent, sustained attention is applied and sufficient resources are applied, perhaps this time the familiar sentiments can work as promised.

Gregory Simpkins, a longtime specialist in African policy development, is the Principal of 21st Century Solutions. He consults with organizations on African policy issues generally, especially in relating to the U.S. Government. He also serves as Managing Director for the Morganthau Stirling consulting firm, where he oversees program development and implementation. He further acts as consultant to the African Merchants Association, where he advises the Association in its efforts to stimulate an increase in trade between several hundred African Diaspora small and medium enterprises and their African partners.